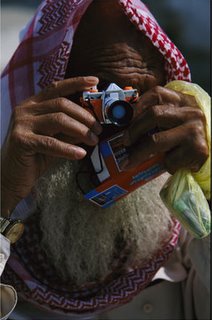

Ra'ad Fadel Salman Ceshkur al-Azawai, a portrait photographer, was shot by US soldiers while standing guard at the Imam Kadhim mosque in Khadimiya on the night of April 10, 2004. The seventh imam, Mousa al Khadim, was martyred and buried there in 799 AD. Khadimiya, a suburb of Baghdad, means the "town of Khadim." Its mosque is the holiest mosque in Baghdad and one of the holiest of the Shiites. When suicide bombers struck it, killing dozens, in March, Ra'ad and a handful of his friends volunteered to guard it. The shooting appears to be a mistake in the fog of war. The passing US Army patrol thought he was an insurgent in the Mehdi Army of radical cleric Moqtada al-Sadr.

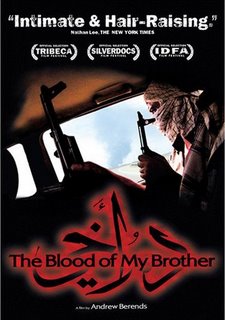

Andrew Berends stumbled into the story a week after arrving in Baghdad, having travelled there from America on a whim. He shot 150 hours of film and made an 81 minute documentary from it, "

Blood Of My Brother." The miracles of this documentary is that Berends was able to travel to Iraq without either a plan or a clue, be invited to document the story of Ra'ad's death a week after he arrived, be accepted by the grieving family even though he was an American, and walk the dangerous streets of Iraq without any security precautions.

Ra'ad was the eldest son and head of his household, which included his mother, brother, and two sisters. His tiny portrait studio provided for them. The documentary follows the younger brother, Ibrahim, as becomes head of the household. It also shows the family grieving, insurgents fighting American troops, prayers at the mosque.

The documentary does not have much of an arc of story, lacking any resolution. What makes it remarkable is that it takes you into the lives of Iraqis and shows the war from their perspective. It's a gang war, basically. American tanks look something like those Martian machines from "War Of The Worlds" from the Iraqi perspective. The insurgents come and go fairly freely through local homes, hiding from the Americans. They see it as a religious war, not a nationalistic war.

Seven thousand mourners showed up for Ra'ad's funeral. They saw his passing as a good death, dying as a hero and martyr in defense of their faith. All the men aspire to such martyrdom. Says one young Iraqi man, "I swear to Allah the Almighty. I swear by the blood of these martyrs. I will never quit. I will never quit until I earn my martyrdom, God willing. And that's what we all wish."

Ibrahim is something of a metaphor for Iraq. He's none too bright nor competent but he has suffered a legitimate wrong though done to him in error. He feels the need for revenge but can not because he must provide for his family. Says Ibrahim, "American people are not guilty but when I see an American or a Jew, I want to kill him because I lost two, I lost two, and American people sleep comfortably but there are planes and tanks all around us. What is this? This isn't life?"

It doesn't occur to any of these Iraqi men that their determination to become martyrs for their religion keeps their environment violent.

The mosque helps radicalize young men like Ibrahim by telling them that America and the Iraqi government are infidels, that they can not have two loyalties, that they must be loyal to Islam, and Islam is best represented by Moqtada al-Sadr and his Mehdi Army. You can see that Iraqis feel little for Iraq. Their loyalties are more local.

Ibrahim doesn't succeed at his brother's photo shop. He can't turn a profit. The crushing blow comes when a man comes to collect a loan his dead brother Ra'ad took out for 250,000 dinars. That's almost $200. Ibrahim has no hope of paying it. He blew a million and a half dinars on Ra'ad's funeral, about $1000, all he had. He's forced to sell the shop to pay off the loan. Now he has to hire himself out as a laborer. On such small sums, fortunes turn in Iraq.

From a text used to teach ninth-graders in Saudi Arabia called "Commentary on Monotheism" by Sheikh Muhammad Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab, printed in 2005-6, Chapter 12, page 100:

From a text used to teach ninth-graders in Saudi Arabia called "Commentary on Monotheism" by Sheikh Muhammad Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab, printed in 2005-6, Chapter 12, page 100: