It looks like an apartment building, and a nice one at that, except that all its residents seem to be fit young men in their prime. A closer look at the men congregated at the entrance reveals half of them standing on prosthetic legs. It is a bracing sight.

It is a guest house for ambulatory patients at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC. When wounded soldiers recover enough in the main hospital to make it to their treatments unaided, they move to a guest house on the grounds or outside. They check in to the equivalent of an efficiency apartment, equipped with appliances including a DVD player and laptop. It’s easier on their wives, too, who can sleep in a bed with their husbands instead of balled up uncomfortably in a chair next to their husbands’ hospital beds.

The spacious foyer, lit by a chandelier, is like those of upscale apartment buildings in one of DC’s nicest neighborhoods. The carpet is rich and padded, better than the carpet trod by the generals in the Officer’s Club a few miles away in Fort Myer by the Pentagon. But then, the wounded outrank the generals.

The foyer holds more wounded troops in civvies. They’re still learning how to use their legs, so they walk a bit stiffly and awkwardly. Some have wounds to the head. Oddly enough, most of them are in a pretty good mood. I’m told that the more seriously wounded, the better attitude they have. I’m the only guy in the joint who can’t stifle a tear.

A guy next to me talks matter-of-factly about his son’s amputation next month as cute little kids chase each other around the legs of the adults. Some of the kids are there to visit their wounded mothers, like the one shot in the face or the other who had her foot amputated. It’s an equal opportunity war.

I came with a group of private citizens who make runs to the guest house several times per month to bring snacks, bottled water, Cohiba cigars, clothes, and other stuff to the troops. The wounded often need clothes, because they are transported directly from the battlefield to hospitals where their clothes are cut off to treat their injuries. They arrive at Walter Reed with nothing, not even a shirt on their backs.

Some families are too far away to comfort their wounded sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives in person so these private citizens fill in for them. They are often the first civilians seen by the troops when they return to America. It’s important to make contact with our guys, some of whom are gravely wounded, and act naturally, give them encouragement. While the hospital handles the patients’ physical recovery, there is their psychological and emotional recovery to consider as well.

This effort kicked off through casual conversation with soldiers at the hospital. One of the guys, a 21-year-old soldier, got to talking with folks visiting from outside and it developed into a regular thing over the course of a year. The folks pay for it out of their own pockets.

Once in a while, radical leftists find a way in to propagandize the patients with anti-war rhetoric. Code Pink visited on Mother’s Day to hand out pink flowers bearing anti-war slogans. It’s the last thing the wounded want to hear, that their sacrifice was made for nothing. Code Pink has been protesting the war at Walter Reed, of all places, for the last eighteen months. They are hotly despised by people at Walter Reed.

The soldiers recovering at Walter Reed have little use for Cindy Sheehan. One soldier in bad shape made his mother promise that if he should die she would not do a Sheehan on him. The mothers, proud of their sons fighting for America, take a dim view of Sheehan’s shenanigans, as well. Said one mom at the guest house, “Dad gum if somebody is going to take the honor of my son away.”

Many of the soldiers at Walter Reed are baffled by the protesters outside the hospital, wondering why the protesters are protesting THEM. When they get well enough to walk, some meander out the gate on Georgia Avenue to gawk at the protesters to figure it out. A few try to talk to the protestors, but their protest leader forbids that, orders the protestors not to talk the soldiers. The Code Pink protestors literally turn their backs on the incredulous walking wounded so that all the soldiers can see are their signs: “LOVE THE TROOPS, HATE THE WAR” and “SUPPORT THE TROOPS, BRING THEM HOME NOW!” Some love. Some support.

One young Army Ranger, wounded in the legs, had his buddy, wounded in the face and blinded in one eye, roll him out in his wheelchair to the protest to see it for himself. He was a scrawny guy from Pennsylvania who seemed awfully, awfully young to be a combat veteran. Two months previously he had been on his second mission of the day on his second deployment in Iraq in a town I won’t name when his squad approached a suspicious house and prepared to lay down explosives to breach the door, which may have been booby-trapped. Just as they were laying down the explosives, the door swung open and Abdul the Insurgent poked his nose out in surprise to find American troops on his doorstep.

The door slammed shut and the Rangers called “COME OUT” before they charged into the house to reach the bad guys before they could grab their weapons. Down the hall they ran toward an interior courtyard when an insurgent grenade detonated and hit the whole squad. Down they fell on top of each other, returning fire from the floor, when the second grenade hit them hard. The Ranger could not feel his arm nor leg and turned around to crawl back to cover in a room when the third grenade tore up his butt and the soles of his feet. It all took about ten seconds.

The rest of the fire teams filed into the house, taking hits, and kept on coming until the house was secured. It was a fast and furious fight of about five minutes. Insurgents would pop up to toss grenades and disappear, surging out of a tunnel like fire ants. The house was a safe house used to smuggle terrorists into the country.

The medics assessed the wounded, stabilized them, and loaded them on a vehicle where a forward observer was lasing the house, illuminating it with a laser to direct the inbound air strike. As they pulled away, an AC-130 gunship blasted the house to rubble, killing thirty or forty terrorists inside. An exact count was difficult after the fact.

The Ranger was rushed to a military hospital in Iraq, then to Germany, then Walter Reed. He had been hit by Russian grenades, wicked little things full of steel BBs in a sheet metal shell, whose effect is like being shot with a 12 gauge shotgun. Shrapnel to his leg muscles made his legs swell up with blood to three times their normal size. The surgeons at Walter Reed performed a fasciotomy on each leg, slicing open the sides of each calf to relieve the pressure and restore circulation. He could see his calf muscle hanging out and the bone beneath.

The Ranger pulled up the legs of his track suit to show me his scars. He was proud of them. His legs were peppered with tiny dot-like scars from the grenade shot. Ugly red scars about two fingers wide ran down both sides of both calves. The docs say he may not run again, but he will walk for sure. He’s lucky, he says, because there are so many amputees at the hospital. Still he wants to run again so he can reenlist and return to Iraq. His Mom is not crazy about the idea. She was the one who told him about the Code Pink protestors while he was still drugged up.

Said the Ranger, “I’m against the protest over there. I mean, it’s their right to do whatever they want. As far as me personally, I get upset because 99.9% of them have very strong opinions yet they have no idea what’s going on over there. I doubt any of them who are standing on that corner tonight over there have actually talked to somebody who lives in Iraq about how they feel over there yet they have all these strong opinions.”

The Ranger has spent a lot of time in bed watching CNN and doesn’t recognize the Iraq it depicts. He sees a lot of anti-American Iraqis on CNN. Most of the Iraqis he met were pro-American except for the terrorists he fought. Says the Ranger, “They don’t show the guy who cleans our bathroom who says, ‘Go Bush, John Kerry bad, bad,’ during the election. They don’t show the dozens of times when I’m walking down the street, going to do a mission and the women on top of the roofs are saying ‘Americans, we love you.’ They don’t show that on CNN.”

~~~

“My son got shot.” It’s a startling introduction to Debbie, standing in the foyer of the guest house at Walter Reed. She’s a nice Southern lady who woke up in her home outside Atlanta one July morning at 7 AM to find that somebody with an 888 number had called her eighteen times while she slept. Curious, she called the number back to find that it was her son’s task force in Afghanistan who transferred her to his commander who told Debbie, “Your son’s been injured.”

Her son, David, was riding a Humvee as the gunner in a convoy of ten Humvees when he was shot through the neck. He survived because the only medic in the convoy happened to be riding in his Humvee and immediately treated him before he could bleed out. That was July 29, 2006, a Saturday.

The military flew David to Germany for surgery. He called his Mom after the operation, still groggy from the anesthesia. “I’m fine,” he said. “I’m numb all over.” He wasn’t really all that fine. He had been paralyzed immediately after being shot, having fallen hard inside the Humvee, suffering a hairline fracture in his neck. He was flown on to Walter Reed.

Debbie earns a nice living creating balloon art for her employer. Her coworkers pitched in to pay for her airline ticket to Washington. She boarded a jet to DC to comfort her baby.

Scott, David’s step-dad, took the news hard. Scott is a veteran of the Army’s 5th Special Forces, had served in Vietnam, and was shot there in the right knee in 1973. He and seven of his hometown friends had all enlisted together. Scott was the only one to return home alive. Having his son shot dredged up all those bad memories he’d rather forget. Going to the hospital was hard for him.

The hospital was full of horrible spectacles. One guy had an RPG stuck in his hip which, thankfully, had not detonated. Two other guys were nearly burned to death in a Humvee. Another guy had a dent in his head the size of a dinner roll, later restored to a normal appearance. Yet another had part of his head blown away so that it looked like a triangle.

David made an amazing recovery. He was shot on a Saturday, transported to Walter Reed on a Tuesday, where he was released as an out-patient on Thursday. By the time he arrived at Walter Reed, he was up and about, joking around. It’s not a complete recovery. David has a brace on his neck and his left arm remains paralyzed. He’ll need therapy to regain partial use of it.

And there is the pain. David has terrible pain in his left arm due to nerve damage. He’s on pain meds which do the job some days but other days they don’t. Some days he just stays in bed until the pain passes.

The scar on David’s neck is tiny, the rifle bullet having drilled neatly through it. That was lucky. AK-47 bullets are built to tumble, transferring all their energy to their targets to tear them up. David may have been shot too close to give the bullet time to tumble, carrying the bulk of its kinetic energy with it when it left his neck. David credits his Mom’s lucky bandana for his survival. The doctors told him they could improve the appearance of that scar but David likes the look of it.

David returned home to Cobb County a hero. Cobb County is the home of the Big Chicken, a fifty-six foot tall sheet metal chicken that has been a local landmark since the ‘60s. For a few days, David was bigger than the Big Chicken and that’s saying a lot.

The local newspaper wrote a story on him. His church, the Open Bible Tabernacle, received him in triumph. David could not walk into an Arby’s nor Taco Bell without the customers picking up the tab. It was a wonderful homecoming.

The only problem was the construction crew working next door to David’s home. When he was lying in bed, he flinched every time he heard their nail gun, which sounded like gunshots. It drove him crazy, that nail gun. He wanted to crawl under his bed to get out of the line of fire.

It is odd for David’s parents, too. They are a military family. Scott, of course, is an Army vet. Debbie served in the Coast Guard for eleven years. At one time, five of her family were serving in the Coast Guard simultaneously. Her Dad was a Master Chief Yeoman in the Coast Guard. Her parents are buried in the Punchbowl National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in the crater of an extinct volcano on Oahu, Hawaii along with the dead from Pearl Harbor and the Pacific theater of WWII. It’s not far from Waikiki where the tourists happily splash on the beach without a care in the world. The old Hawaiians called the Punchbowl “Puowaina,” the “Hill of Sacrifice.”

The problem for Debbie and Scott is that few of their friends have served in the military. Their friends’ lives roll on undisturbed by the war in any way. They don’t understand the sacrifices military families make in peacetime, let alone wartime. When a soldier is wounded, it wounds his whole family. They live with the damage long after the war is wiped off the front pages.

Their poise in dealing with this blow is based on their faith. David was raised in the church by his parents and though he is reserved about it, his faith runs deep. When he was shot, he had stored up a well of faith he could draw upon. He would tell Debbie, “Mom, just keep praying and it will all work out.”

David is back in the guest house to continue his treatment. He’s talking about going to school to be a pediatric neurologist but mostly he plays video games all day. Many of the wounded combat vets are just big kids, playing with their Game Boys. David wants to get well so he can see his girlfriend, Jess, if you know what I mean.

The Secretary of the Army is coming to pin the Purple Heart on David, among other patients, though there is a rumor that the President himself may do it. He’s jazzed about that. Debbie has been waiting on him hand and foot, but now David is playing the Purple Heart card on her to wheedle even more favors from her. Mom knows a scam when she sees one, but she just kinda lets it slide and goes along with it. She walks around the guest house sporting a big button that says, “My Son Is Serving Proudly In The Army. Pray For Peace.”

David and his Dad, Scott, rented a car to get out of the hospital and see the sights of DC. They parked near the National Mall and slowly made the long walk to the Wall, David in his neck brace and Scott on his artificial knee. There they read the names chiseled in the Vietnam Memorial and probably saw in it their own reflections, princes of America’s natural aristocracy of patriots.

Randall Barnhart, 62, and his wife Carole, 61, were rudely awakened at 2 AM by shouts in Malay and pounding on the door of their rented condominium unit in Langkawi, Malaysia. When Barnhart cracked the door, he found six Malays dressed in blue jackets with a government department crest on their breast pockets. One produced identification from the Islamic Affairs Department.

Randall Barnhart, 62, and his wife Carole, 61, were rudely awakened at 2 AM by shouts in Malay and pounding on the door of their rented condominium unit in Langkawi, Malaysia. When Barnhart cracked the door, he found six Malays dressed in blue jackets with a government department crest on their breast pockets. One produced identification from the Islamic Affairs Department.

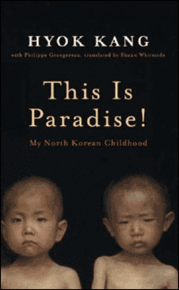

Hyok Kang

Hyok Kang